What is copyright?

Copyright is a form of protection that the United States laws give to the authors of original intellectual work. Works included in this category are music, literature, pantomimes, choreography, dramatic works, pictures, graphics, sculptures, motion pictures, audiovisual work, sound recordings, and architecture. Copyright is acquired when the work is fixed in any media for the first time; no further actions are necessary to continue to keep this right. The Copyright Act of 1976 gives the owner of the work the exclusive right to reproduce or copy the work, distribute copies, perform publicly, publish the work and elaborate extension work based upon the initial product. It is against the law to use copyrighted material in the areas protected by the Copyright Act, but some uses of the copyrighted work are permitted after paying royalties.

Any creator of work is the owner of the copyright except for work “Made For Hire,“ which the work prepared by an employee within the scope of his employment.

Ownership of someone else’s work, for example, a book or a music disc, does not make the possessor the owner of the copyright. Copyright protection is also available for work that has not been published independently of the nationality of the author. Works published before January 1st, 1923, is in the public domain. These works are too old to qualify for copyright protection.

Many materials cannot be copyrighted, for example:

– Any work that has not been written or recorded. – Titles, names, phrases, slogans, family symbols, colors, or list of ingredients. – Ideas, procedures, methods, systems or processes. – Work consisting of information of common property or no original work . – Intellectual work made by animals is not eligible to be protected by Copyright. Examples of that work are: “a photograph taken by a monkey” and “a mural painted by an elephant” (U.S. Copyright Office, 2014). The office of copyright stipulates that only works “created by a human being” can be registered for copyright.

The importance of publication in the Copyright Law.

Publication is not necessary to obtain federal copyright although many authors still think that publishing is crucial to ensure their copyrights. The U.S. Copyright Office defines publication as the distribution of copies to the public, transfer, sale, or rental with no restriction concerning its contents. “A public performance or display of work does not constitute publication” (U.S. Copyright Office, 2014).

Publication is important for the following reasons:

– Published works are mandated to have a copy in the Library of Congress.

– Publishing work affects the rights of the copyright owner.

– The year of publication determines the length of copyright protection.

– Deposit requirements are different for published than for unpublished works.

Copyright notice

Works published before March 1, 1989, are required to have a copyright notice or have the risk to lose the protection. Currently, published work may include a notice with information as the name of the copyright owner and the year of publication. A notice of copyright although not required it is beneficial. This notice was required in under the 1976 Copyright Act but eliminated when the United States joined the Berne Convention on March 1, 1989. For unpublished work, the author has the option to place a copyright notice to protect work that leaves her hands. The use of a copyright notice does not require permission or registration with the Copyright Office.

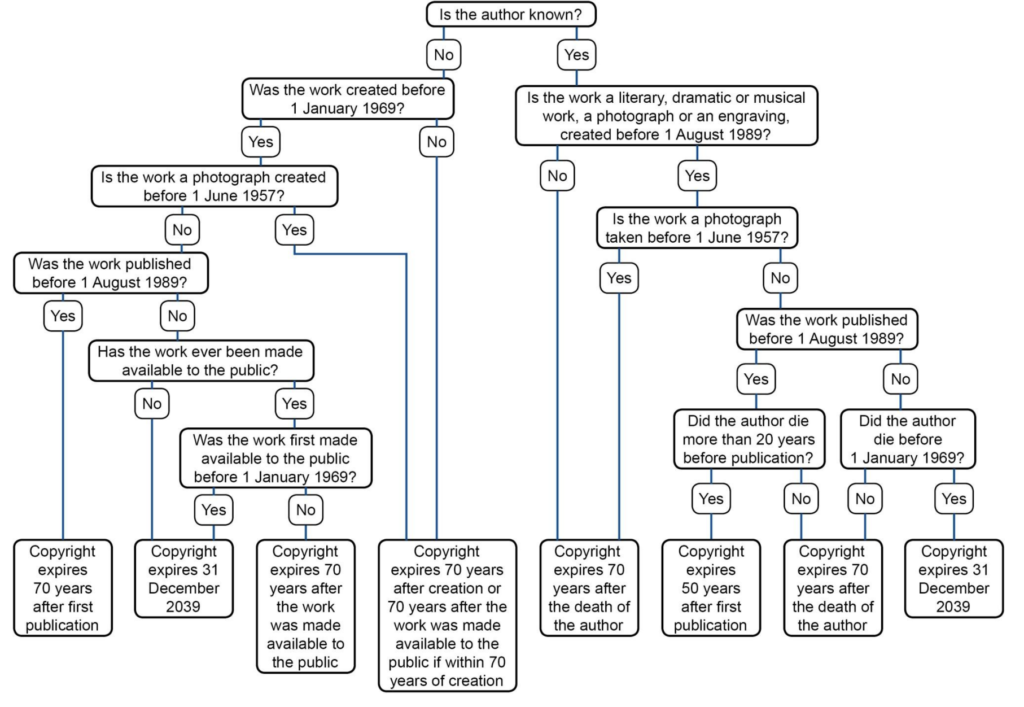

Copyright length of protection

Copyright protects any work created after 1978; the term of its protection is the life of its author plus 70 years. For other works like those made under hire or anonymously, protection will last 95 years from publication or 120 years from its creation whichever is shorter. Any copyrighted work can be transferred by establishing a written and signed contract, just like any other physical property. The Copyright office must have a record of the transfer. For more detailed information see the chart below.

Fair Use – The Great Dilemma

The Copyright Law includes the so-called fair use, which was given by section 107 of the 1976 Copyright Act. It allows the use of copyrighted materials for specific purposes, according to McCord (2014) “Using a copyrighted work in a fair way does not infringe the copyright in the work.” The question would be what kind of use is fair? There are four factors that we can use to determine if the use of a specific intellectual work is fair. The use of these factors is called the 4 Factor test.

Factor 1. Will the work be used with commercial purposes or nonprofit educational use? Rephrasing this question will get us to understand its purpose better; for example, we could say to what degree the use of this work will contribute to someone’s education? To what extent will this work help produce income?

Factor 2. What is the nature of the copyrighted work used? Is it informational or for entertainment?

Factor 3. What portion of the total work will we use? Why are we using that specific portion?

Factor 4. What will be the effect of our use on the market of the original work? Will potential paid users change their mind due to our actions?

The Fifth factor

Transformative Law. It first appeared in a Supreme Court decision in 1994, and since then it has been part of the Fair Use Law. “A derivative work is transformative if it uses a source work in completely new or unexpected ways” (University of Minnesota, 2019). Following the transformative law, we can use someone’s work as long as it is transforming the purpose of it, for example, making a parody, mixing and remixing can be considered transformative work.

Performing the Five Factor test involves a risk assessment. It is crucial to make ourselves the following question: How risky is for us to use the work that we are intending to use in the way that we are planning to use it? The most significant problem with fair use is that it is not clear-cut and there are many gray areas.

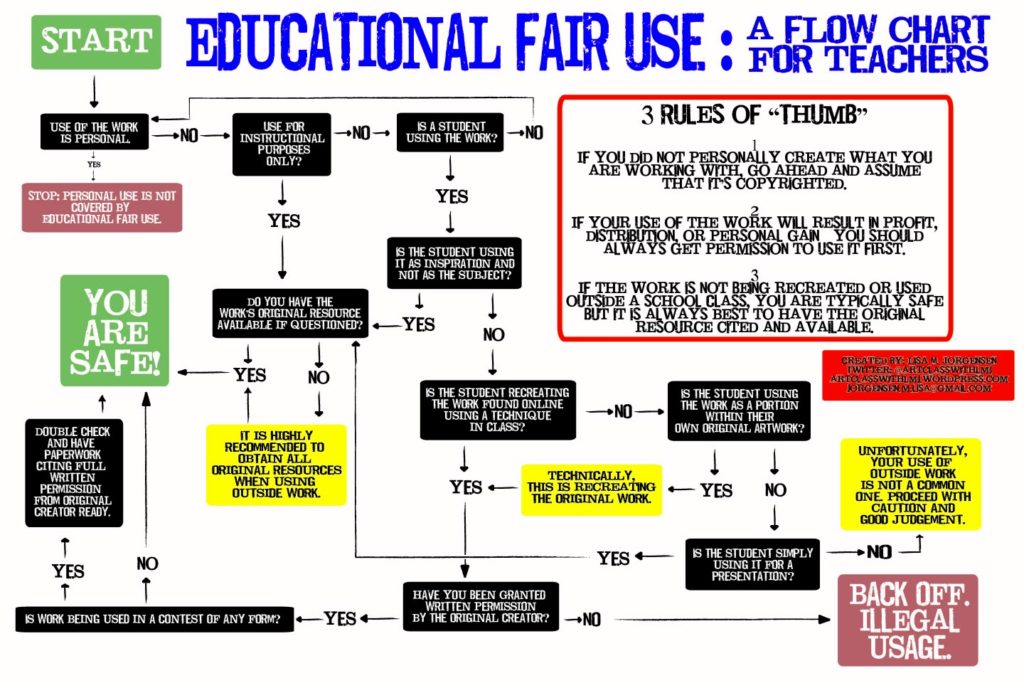

Fair use for Education

Teachers and students have special privileges when working with copyrighted materials if the use is for education, with no commercial purposes but still is a complex topic. Use the chart below to determine if the use planned falls under fair use.

Another great resource to determine what can be used for educational purposes is the Copyright and Fair Use Guidelines for Teachers document from techlearning.com.

Copyright infringement and plagiarism

Copyright infringement is to use the intellectual property of others in a way that is not permitted. For example, making copies of software bought for personal use for all students in a class to take home. Plagiarism is to present someone else’s ideas or work as own. For example, finding an article online, copy paste a section and use it without citing it, making it appear as if those were our ideas. To avoid plagiarism, good use of attribution is a must. Attribution is the practice of citing someone else’s work (Buttry, 2019). Telling the audience the source of information increases credibility.

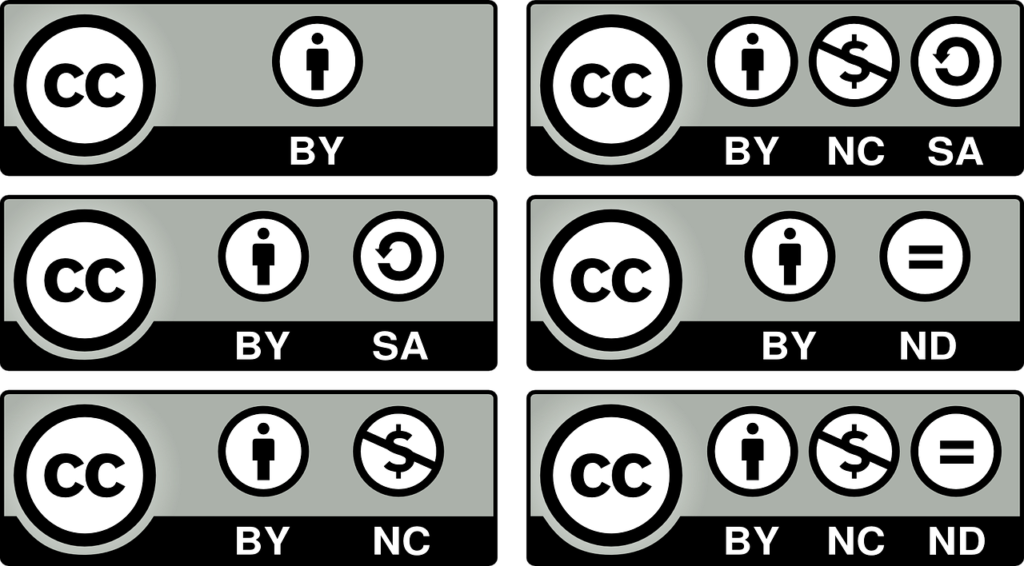

Creative Commons

Nowadays, authors have the option to legally share their creations in various ways. One of the highest goals of creative commons is to develop a world where information is more accessible for everybody, increasing the development of creativity; this is the principle in which Creative Commons is based. Its goal is to make free standardized copyright licenses to permit the public to use your work under certain conditions that are previously specified while still preserving copyright of the work and getting the credit that the author deserves. Visit the Creative Commons web page to learn more about the types of licenses available and how to choose the most adequate to your needs.

References

Baily, J. (2013). The difference between copyright infringement and plagiarism. Plagiarism Today. Retrieved from: https://www.plagiarismtoday.com/2013/10/07/difference-copyright-infringement-plagiarism/

Buttry, S. (2011). You can quote me on that: Advice on attribution for journalists (blog post). The Buttry Diary. Retrieved from: https://stevebuttry.wordpress.com/2011/10/31/you-can-quote-me-on-that-advice-on-attribution-for-journalists/

Creative Commons (n.d.). About the licenses (web page). Retrieved from: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/

Mccord, G. (2014). Fair use: The secrets no one tells you. Retrieved from http://www.digitalinfolaw.com/fair-use-the-secrets-no-one-tells-you.html

Tepp, S. & Oman, R. (2015). A 21st century copyright office: The conservative case for reform (white paper). Hudson Institute, Center for the Economics of the Internet. Retrieved from: https://goo.gl/rdyxxV

The University of Minnesota Library (2019). Copyright services (web page). Retrieved from: https://www.lib.umn.edu/copyright/fairuse

United States Copyright Office (2012). Copyright basics (circular 1). Retrieved from: https://goo.gl/GPEXtm